chris ofili: night and day at the new museum

Chris Ofili. Untitled (Afromuse), 1995–2005; watercolor and pencil on paper; 9 ⅗ x 6 ⅕ in. Courtesy of the Artist; David Zwirner, New York/London; and Victoria Miro, London.

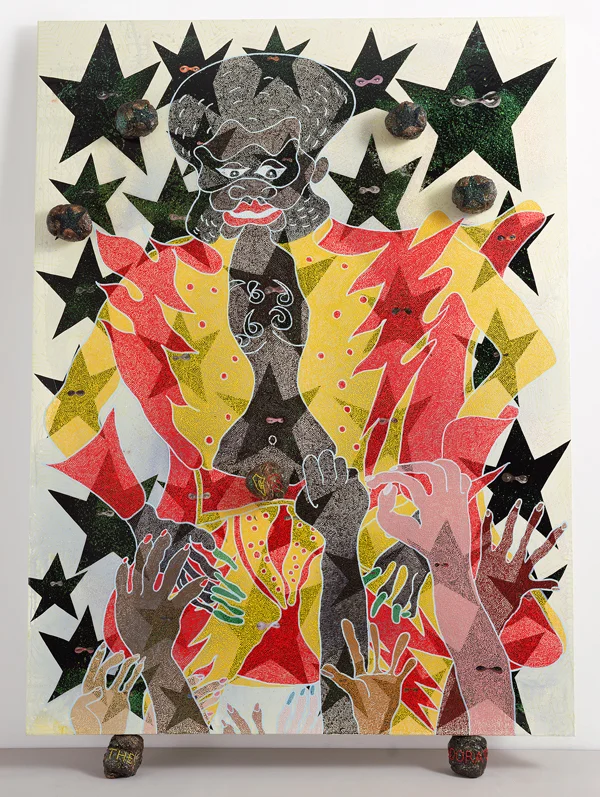

Chris Ofili. The Adoration of Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars (Third Version), 1998; oil, acrylic, polyester resin, paper collage, glitter, map pins, and elephant dung on linen; 96 x 72 in. Courtesy of the Artist; David Zwirner, New York/London; and Victoria Miro, London.

Daily Serving

November 20, 2014

Night and Day at the New Museum is the first retrospective of the artist Chris Ofili in the United States. While the show incorporates sculptures and drawings, it unmistakably showcases the artist’s bravery, skill, and reinvention in painting over the past thirty years. The six bodies of work that span three floors are fearlessly distinct; clearly this is an artist who has no interest in repeating himself or sticking to a singular style. What unites all these works, however, is the cohabitation of conceptual rigor and an unwavering commitment to beauty. Each work is accessible and visually engaging to anyone willing to look. Longer contemplation unearths Ofili’s rich and ambivalent meditations on black identity, consciousness, and representation.

One of the artist’s strategies for striking a balance between content and form is to enforce constraints upon his process. Afromuses, a series of over 100 small watercolor portraits of imaginary black individuals, provides one example. From afar, these same-size works on paper look almost identical, rendering the same criteria: the hair, face, neck, and chest of a figure seen frontally or in profile. Within these parameters, however, is tremendous experimentation with color, pattern, and technique. These are quick studies, each done in fifteen to twenty minutes, but they reveal the freedom, improvisation, and inspiration Ofili finds within his self-imposed restrictions.

Similarly, the infamous elephant-dung paintings exemplify the challenges the artist promotes in his process. In a recent talk with the museum’s curator, Massimiliano Gioni, Ofili described his choice to experiment with dung in his work as a contradiction that felt strange but useful.[1] The dung, which the artist first collected while on a residency in Zimbabwe, makes reference to Africa as both context and myth. Its material nature is so distracting, though, that the potential for beauty is nearly destroyed. Ofili’s self-constraint in this case is essentially ruining the painting from the get-go, to test his skills with composition, pattern, decoration, and intensive detail—to not just counterbalance but also overcome the shit. And overcome it he does.

All of the paintings rest on dung balls, each decorated with letters that spell the title of the piece. This presentation elevates each painting off the floor and allows the canvas to lean against the wall. The works not only feel more three-dimensional but also boast their opulent surface ornamentation. Rodin…The Thinker is loaded with ornate, swirling organic patterns covering the central figure and background. Ofili reinvents the famous sculpture’s pose by making the painting’s subject a black woman with orange hair, clad in an orange thong, thigh-high stockings, and garter belts. While the work does reiterate a trope of the sexualized black female body, it does so while recasting an icon of the white male philosopher/poet.

Many of Ofili’s paintings contain this heady ambivalence, simultaneously playing with allusions to both marginalizing stereotypes and empowered figures. Several of the dung paintings depict a superhero of Ofili’s invention named Captain Shit, an amalgam recalling figures like Shaft and Superfly from blaxploitation films and Luke Cage, one of Marvel Comics’ first African American superheroes. The Adoration of Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars (Third Version) shows Captain Shit performing before an adoring crowd. Black and white hands are raised in excitement before him, and large black stars in the background contain collaged cutouts of eyes gazing upon him. The Captain Shit paintings suggest the fervor and self-consciousness of celebrity culture but more specifically the multivalent experience of being a black figure in the public eye. The subtext of these works is an exploration of a contemporary minstrelsy and the mixed blessing of having talents that propel one to prestige and prominence, with the caveat that a large portion of the audience may uncritically consume, fetishize, or parody one’s identity.

Another series shares the lavish and intricate techniques of the first set of dung paintings but applies a new constraint: a limited color palette. Created for the 2003 Venice Biennale, when Ofili represented Great Britain, these five paintings are executed in black, red, and green, the colors of Marcus Garvey’s pan-African flag. Afronirvana portrays reclining figures amid a tropical landscape. Lush leaves frame the figures, and hanging above the center like a North Star is a dung ball adorned with a red, green, and black pattern. The figures are akin to the Afromuses: at once anonymous and specific, mythically regal, yet unpretentious.

The third floor features nine paintings in a dimly lit, carpeted gallery, with a constricted palette of deep indigoes, blacks, silvers, and purples. The limited range of tones veers to the point of invisibility. From oblique angles, one begins to discern the dark scenes, some nightmarish: a body hung from a tree, police circling a figure on the ground. These works present a troubling rumination on race and visibility, forcing viewers to reconcile themselves to what their imaginations kick up in the struggle to decipher each image. Here, Ofili throws away all the intoxicating stylistic charms that brought him notoriety, yet these works still reference a chromatic spectrum and preoccupation with beauty that has rippled through much of Western art history, from Renaissance frescoes to Picasso.

On the final floor of the exhibition, the artist painted a floor-to-ceiling backdrop of lush, watery, pink and purple tropical wildlife, inspired by the 1947 film Black Narcissus. Amid this expanse are nine paintings, all loaded with rowdy color and form, like players in an immersive set. There is no concern or allegiance here to contemporary trends or dialogues surrounding painting; these compositions are throwbacks to Matisse, Gauguin, and color-field painters, all sampled with nerve and control. This may be Ofili’s best trait: his receptivity to influence—be it from the art-historical canon, hip-hop, pop culture, cult films, or Romanticism—all while maintaining a focused and nuanced exploration of black life and representation.

Chris Ofili: Night and Day is on view at the New Museum through January 25, 2015.

[1] New Museum, “Chris Ofili and Massimiliano Gioni in Conversation,” embedded video, “Chris Ofili: Night and Day,” http://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/chris-ofili.

Chris Ofili. Afronirvana, 2002; oil, acrylic, polyester resin, aluminum foil, glitter, map pins, and elephant dung on canvas; 108 x 144 in. Courtesy of the Artist; David Zwirner, New York/London; and Victoria Miro, London.